Australian historian and author

Mum would occasionally respond to her children’s naughtiness with the expression: ‘Butter wouldn’t melt in your mouth’. It was an affectionate call out – notice that one of us had been sprung and were acting as if nothing had happened. We were a pretty well-behaved lot so the transgressions were minor.

The notion that one could be so cool in the act of deception or disingenuousness that a nugget of butter might stay solid in the gob is an old one. It long predates refrigeration, oddly enough. My wonderfully tactile second edition of the Oxford Dictionary of English Proverbs [1963] dates it to John Palsgrave’s 1530 book on French grammar. The term may therefore have continental origins but I suspect it was a local saying, already familiar and used by Palsgrave to assist his readers understand French. My English mum knew it well enough.

In either case the proverb refers to the practised dishonesty of the subject. And so it came to mind when I read the transcript of Josh Frydenberg’s speech to the Australian Industry Group a couple of weeks ago, titled ‘Capital markets and the transition to a low emissions future’. The Australian Treasurer’s chat was an upmarket assessment of what many scientists view as an impending catastrophe. It ended thus:

Climate change and its impacts are not going away. It represents a structural and systemic shift in our financial system, which will only gain pace over time. For Australia, this presents risks we must manage and opportunities we must seize. That work is well underway but there is still more to do. (24/9/21)

One wonders about the timing and content of the address. Scientists, environmentalists, and indeed many economists, have been pointing to the costs of not adapting to inevitable climate change for a decade and more. It has long been recognised that ‘climate change and its impacts are not going away’ and preparing for those makes good financial sense. Environmental issues no longer sit conveniently outside the market as irrelevant ‘externalities’, in the modelling of neo-classical economists, they are inconvenient truths which must be factored in. Surely something more leaderful would be have been appropriate from our Treasurer as we head, ever faster, towards the cliff of disastrous climate change.

Australia’s Coalition of the Liberal and National Parties – to which Frydenberg has belonged since 2010 – generally defers to market forces. Government regulation, taxation, interference is anathema to their vaunted defence of the individual and the family. They were even willing to let car manufacturing die in Australia. The last locally-built Holden – that symbol of this nation’s post-war industrial recovery – rolled off the assembly line during their tenure in 2017. Market forces simply demanded it.

And yet they have waged a culture war against the science of climate change since 2009 when Tony Abbott unseated Malcolm Turnbull as the leader of the then Coalition opposition. The opening salvo in that conflict was Abbott’s reference to the scientific predictions as ‘absolute crap’. His ensuing wholesale opposition to Government policy mirrored the tactics of the US Republicans against Barak Obama’s reforms, and helped him win Government in 2013. Dealing with climate was characterised as a typical Labor effort to raise taxes on hardworking families. It was something that only elites, detached from the real world of suburbs, farms and the regions around them, worried about. The popular consensus developing around the need to address climate change was eroded in the process.

The Coalition has been in power ever since, and ever since they have opposed effective action on climate change. In 2014, former treasurer Joe Hockey referred to wind turbines as ‘utterly offensive’ blots on the landscape without any sense of irony; of course, the term would be better applied to open cut coal mines. Major climate change rallies in Australian cities in 2015 were dismissed as manifestations of the selfish hysteria of urban ‘elites’. In the lead up to the 2019 Federal election, small business Minister Michaelia Cash furiously argued that electric vehicles would be imposed upon Australians by an authoritarian Labor government – thus crippling the businesses and families dependent upon gas-guzzling pick-up trucks and SUVs. In 2019 the office of Energy Minister Angus Taylor sent false information concerning the climate conscious Lord Mayor of Sydney, Clover Moore, to the right-wing media in an attempt to embarrass her. In 2020 former resources minister, Matt Canavan, referred to renewable energies as the ‘dole bludgers’ of the energy sector compared to hardworking coal.

But most theatrical and outrageous of all was [then Treasurer] Scott Morrison’s goading of the Labor opposition in parliament in 2017. Then he waved around a large piece of coal, helpfully provided by the Minerals Council of Australia, while shouting, ‘This is coal, don’t be afraid, don’t be scared’. The message: climate change is a figment of paranoid imaginations.

There was no mention of that litany of absurdities in the Treasurer’s recent rosy assessment. Indeed, he dutifully trotted out the creative accountancy which scores Australia high for its emissions reduction efforts, as he has done on previous occasions. All other credible commentators take the opposite view. With the defeat of Donald Trump in the US, Australia’s sorry record on climate change has become increasingly difficult to justify – hence Frydenberg’s recent anodyne address I suspect.

The melt off the West Antarctic Ice Cap has tripled since 2000. The pace of glacial disappearance is similar in Greenland and elsewhere. Sea level rise, shifts in ocean currents, increased severe weather events, bushfires and extinctions are following the disappearance of ice – just as scientists have predicted they would.

Yet instead of preparing Australia for the changes, or assisting with global efforts to lessen the catastrophe, since 2009 the Coalition has obfuscated and politicised an issue which affects everyone. More than a decade has been lost because of the so-called ‘climate wars’. As the ice melts across the world, the Australian government is being pulled unwillingly towards meaningful action. They won’t admit to fault of course – butter wouldn’t melt in their mouths.

Visiting a place one intends to write about makes an immense difference. It really does. I spent three weeks in Papua New Guinea [PNG] in September trying to get a feel for the country that Australia ‘ruled’ as a colony from 1905 – that was Papua – and a territory from 1919, New Guinea. PNG came into being in 1949. The trip was background for my upcoming history of Australia and the Pacific. The CH Currey Fellowship from the State Library of New South Wales certainly helped to fund it; PNG is an expensive place to visit.

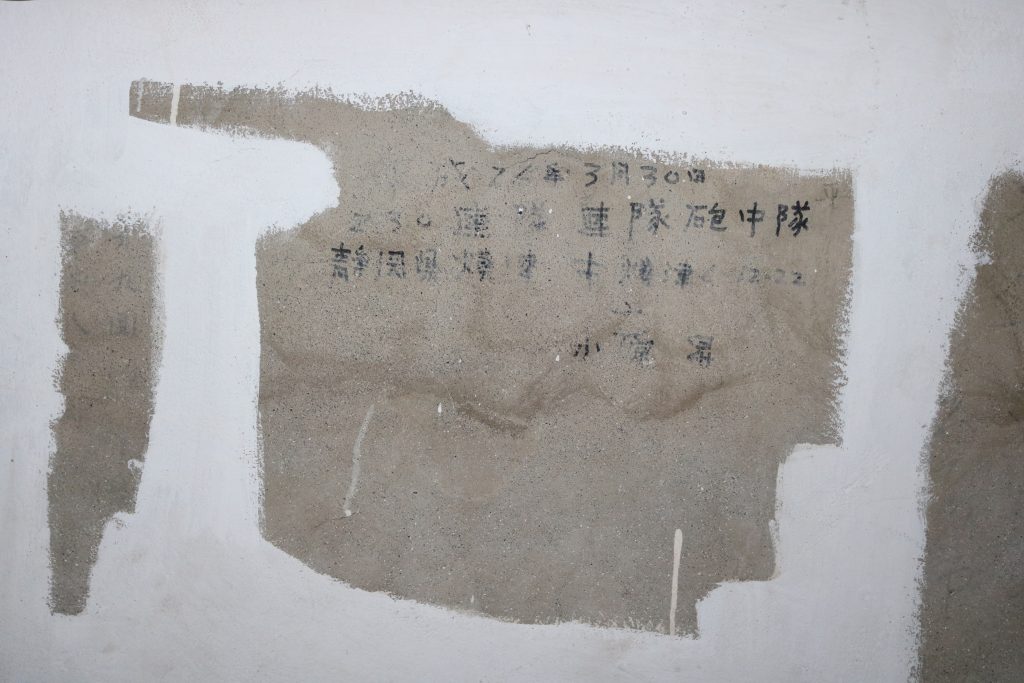

I was four days in Rabaul trying quickly to get a sense of the town which the Germans built in 1910 as the capital of their Pacific colony, the Australians took over in 1914 and made the centre of their League of Nations Mandate from 1919, the Japanese captured in January 1942 as the forward base of their Pacific campaign and the Australians reclaimed in 1945. What was left of old town after Allied bombing was destroyed 49 years later by a volcanic eruption. Four days was not long enough but I covered a lot of ground and had read up in preparation.

The papers of Kenneth Thomas, copied from the Pacific Manuscript Bureau collection and held at the State Library of New South Wales, describe the town encountered by a cadet patrol officer in 1927. The young Thomas headed straightaway to Rabaul’s ‘Chinatown’ area to be fitted out with his khakis from the tailor Chong Hing. He bought his helmet from Burns Philp, the Australian shipping and trading firm which dominated ‘Australia’s Pacific’ before the war, and for a time afterwards.

The Library also holds the original ‘War Diary’ of Jock Maclean who, as a planter, evacuated his family to Australia in late 1941 when news of war with Japan spread; ‘Many people were about, rushing from one place to another. Everyone seemed dazed’. His family farewelled, Maclean then escaped the Japanese invasion in January with a trek and boat journey to Buna, the very place where the Japanese would later land before the ‘Battle of Kokoda’. It is tempting to describe Maclean’s ordeal as extraordinary but, in 1942, it wasn’t.

The Australian writer Ian Townsend has told the awful story of the execution of 11-year-old Dickie Manson with his mother and her defacto partner at the hands of the Japanese in his book Line of Fire. The American historian Bruce Gamble wrote three books on wartime Rabaul, including Fortress Rabaul which I found really useful. It is also unusual to read an American take on an Australian story. Brett Evans wrote and presented the radio documentary ‘Last Letters’ which told of the Japanese mail drop of letters over Port Moresby written by prisoners captured in Rabaul. What might have been a rare act of humanitarianism by the Japanese turned out to be a more typical expression of cruelty. The prisoners were already dead.

That was home work, but on the ground one really needs a good local guide to suggest places of interest and get to them, particularly if time is short. I am so grateful to the Rabaul Hotel, which survived the eruption, for their useful suggestions. I am so very appreciative of local historian Albert Koni who then took me to Japanese tunnels, airfields, wrecks, museums, execution sites and a submarine base. There I snorkelled along a reef drop off before entering two of five tunnels dug into the volcanic cliff face to store supplies for the subs. The last leg of our adventure had us crunching across the red and black beach of volcanic gravel towards the mountain that erupted and the site of Dickie Manson’s execution, a place identified by Albert after talking to a local man who learned Japanese during the war.

Albert Koni was born in Rabaul, the main centre of East New Britain. His parents were from the Sepik region on the mainland but he claims local Tolai identity by birthright and is recognised as Tolai by others. He trained and worked locally as a butcher and only came to history late in life. Albert takes tours with passengers from the cruise ships that occasionally visit. It must have taken some courage to make that career shift. Albert is deputy president of the local historical society which uses the old New Guinea Club as its headquarters and museum. The pre-war Club was racially exclusive, as were all of Rabaul’s places of entertainment during the Australian administration. I’m not sure if there is irony there but it is certainly poignant. Albert has never studied history formally but his knowledge is extensive. It is matched by his passion and his love for Australia, somewhere he has never visited. That one of his family was tortured by the Japanese has influenced that affection. But he also believes Australia brought modernity to New Britain, and that was a good thing. Albert is a proud Parramatta Eels supporter and wears the football team’s anniversary cap to prove it.

The story of Rabaul during World War Two is Albert’s special interest. He is quite right in believing this is barely known let alone understood in Australia. The battle of Kokoda has been elevated in the Australian collective consciousness so that it rivals, almost, the mythic status of Gallipoli and the Anzacs. But despite the books and broadcasts few who don’t have personal connections with Rabaul, family who served there for instance, know about the tragic story of the abandonment of the 2/22 Infantry Battalion who defended the town along with a few ineffective aircraft and other defence personnel. This was one of the island ramparts that Prime Minister Billy Hughes fought for after World War One. It was, consequently, given to Australia as a Mandated to manage and develop ethically. The men at Rabaul were an ‘advanced observation line’ on that rampart. In the event of an invasion they were to ‘make the enemy fight for [that] line’ in the words of the Australian Chiefs of Staff. But even before the outbreak of war those men knew that the garrison could not withstand the scale of attack that the Japanese could mount. They were right. The defenders of Rabaul were doomed from the start. More than 100 were bayonetted to death by the Japanese with their hands tied behind their backs. A similar number of Tolai people were taken to Papua as forced labour on the Kokoda campaign. I suspect few of them returned.

I asked Albert why he was so interested in history and he came back with something quite poetic and unexpected: ‘The mountain cannot speak’. It is up to people to do the talking, he said. And then cryptically ‘History will sustain you’. The puzzle that is our past will never, of course, be completely reconstructed or understood. But trying to put some of the puzzle pieces together sustains me too.

Thanks Albert.

My previous blog got its title from the call for an expedition to New Guinea by the Honorary Secretary of the newly-established Geographical Society of Australasia in 1883. Edmond La Meslée spoke confidently of finding ‘men of the right stamp’ to head off in the cause of benevolent colonialism. As I work my way through the many books published about the Pacific in the late 19th century its proving hard to find a woman’s voice among all those ‘good men’ who plied the Pacific doing their patriotic duty, saving souls, furthering science or making money… and then writing about it.

Caroline ‘Cara’ David’s account of her visit to Funafuti in the Ellice Islands (today’s Tuvalu) in 1897 is not only unusual because of its female perspective, it is remarkably candid, down-to-earth and free of the worthy pomposity and superiority that characterises so much Victorian travel writing. One gets a sense of that from the title: Funafuti or three months on a coral island: An unscientific account of a Scientific Expedition.

Mrs Edgeworth David, as her name appears in the book, was the wife of the renowned geologist Tannant William Edgeworth David, better known as Edgeworth David. There is a building at my old alma mater, Sydney University, named after him. He was Professor of Geology there from 1891. As was the Australian custom until living memory, married women of social standing were typically referred to by their husband’s entire name – for he was the one who established the standing. So it was with Cara despite her education and profession as a teacher.

Edgeworth David’s intention on Funafuti was to investigate Charles Darwin’s theory of the creation of coral reefs. His Galapagos Islands epiphanies are well-known today, but Darwin’s coral theory is a relatively little discussed part of the famous trans-Pacific voyage in the Beagle. Yet it was a significant step in the gestation of the theory of evolution. Darwin’s 1842 work On the Structure and Distribution of Coral Reefs anticipated the more famous On the Origin of Species published in 1859 by describing the evolution of ecosystems over time, a concept that differed clearly from Biblical creationism in which all life was perfectly made by God in seven days. It also challenged the ‘catastrophism’, the theories of sudden change, expounded by others who were struggling to explain the evidence of apparently displaced rocks, and the fossil remains of creatures long gone, within a paradigm which respected Christian precepts.

I’m guessing Cara and Edgeworth had a close and respectful relationship. As she wrote: ‘my husband said he was going, and politely hinted that I should be an idiot not to go with him. After that there was nothing for me to say’. It was not just, or even, wifely devotion that convinced Caroline to go: Funafuti was, she thought, ‘so intensely interesting’.

British-born Cara and Edgeworth had met on their passage to Australia in 1882, she to take up a post as the Principal of Hurlstone Training College for women teachers and he as the colony’s Assistant Geological Surveyor. They were married in 1885. Caroline’s college was near Ashfield in Sydney’s expanding western suburbs. Edgeworth spent most of his first two years in the field around New England in northern New South Wales. Separation might, therefore, have delayed the wedding.

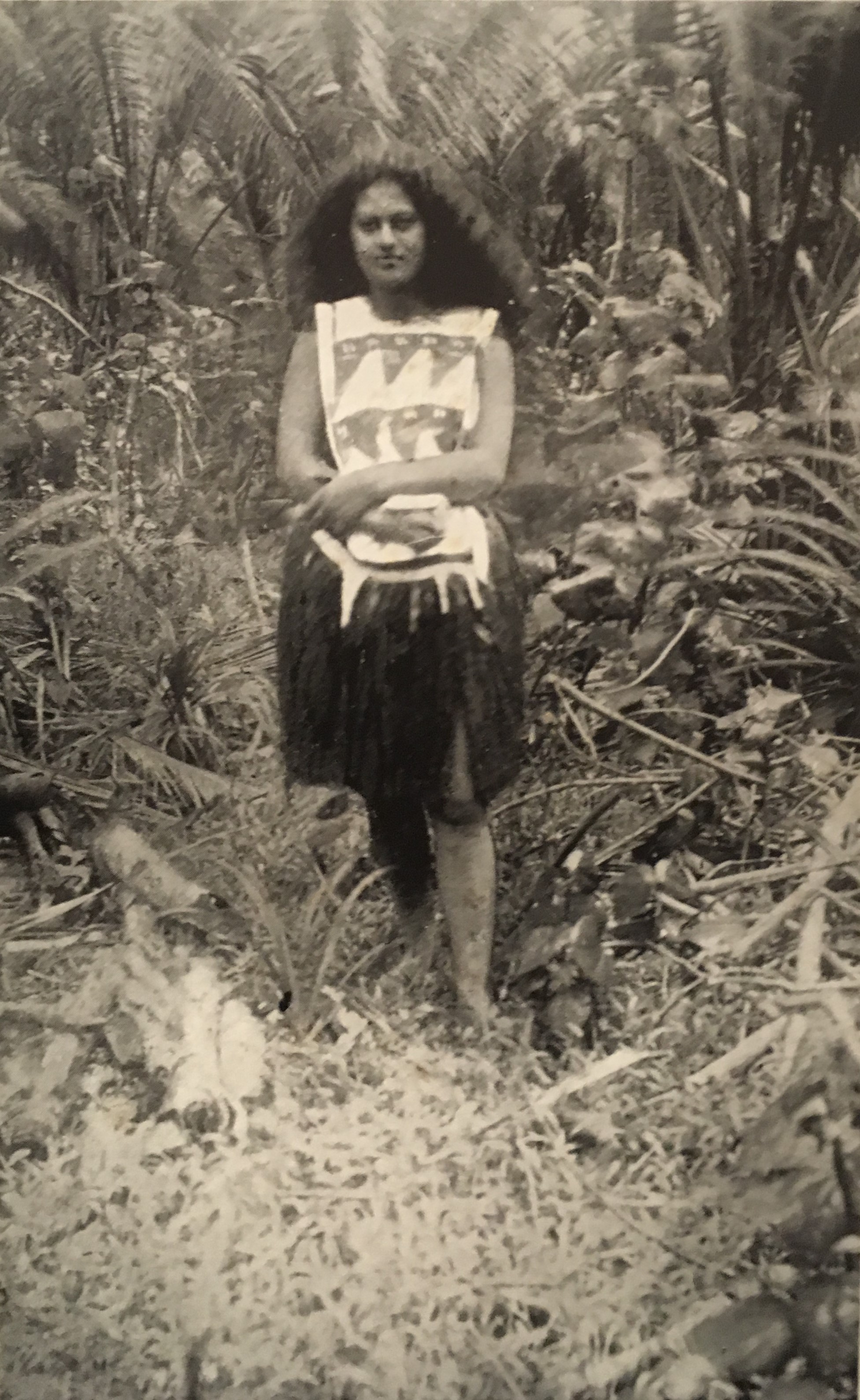

Here is Cara’s description of the travel homework she undertook with Edgeworth: ‘We noticed that no two atlases agreed to the exact position of the Ellice Group… The map labelled the islands British by putting a pink line under the name. Under our own flag, anyhow! And if the black people kill and eat us, we shall be avenged! Unutterable comfort in that thought! We found afterwards that the Ellice Islanders hadn’t the faintest desire to kill and eat us; on the contrary, they were quite as civilised as most white folk.’ My reading of those remarks suggests a woman poking gentle fun at the authority of Empire, the associated certainty of cartographic knowledge and the assumptions about primitive ‘otherness’ that pervaded Pacific writing throughout the century.

The Davids chugged along for eight days in the steamer that took them from Sydney to Fiji. A smaller vessel delivered the party to the Ellice Islands. Having recovered from the sea-sickness endured on that last leg between Suva and Funafuti, Cara set about domestic duties and taking note of the locals. Personal space and seclusion were things she immediately recognised as one feature of British society not shared in the Ellice Islands. Under the scrutiny of the islanders, she craved ‘the privacy of the poorest Englishman’s cottage’.

With Edgeworth out exploring drill sites for the coral core samples, Cara cleaned their allocated hut and arranged it as best she could along the lines of the hygienic, compartmentalised Anglo-Australian home: ‘I spread a layer of clean white coral pebbles [on the floor], and over them again a layer of rough palm-leaf mats, and over all three good pandanus leaf-mats… Then I placed the sleeping-stretchers at one end of the hut and close by them arranged toilet requisites in a packing-case… nailed up cabin pockets and tidies on the posts of the hut, fenced off small areas as hanging wardrobes… selected a centre of the hut for dining room, and turned a packing case upside down for a table; unstrapped my deck-chairs and fell into one with an ecstatic grunt’.

There developed a routine. Cara cooked and cleaned and washed clothes herself. She ‘gossiped with the natives near the drill or in their huts, collected flowers, gathered shells, and bathed in the lagoon’. Conversation was possible at first, no doubt, because of missionary contact but Cara later learned Samoan. She became the island doctor and nurse to both whites and locals, treating ulcers and ringworm and discouraging the eating of pork because of biliousness it apparently caused. There were alternatives to pig. Coconuts were plentiful, vegetables grown in gardens and seafood caught in what seemed like sustainable abundance. ‘Fish generally in Funafuti have a bad time of it’, Cara noted wryly, ‘they are hooked, speared, netted, and trapped, and yet in spite of all these drawbacks they manage to increase and multiply exceedingly’.

Cara went to church, as one may expect, but with nothing like the dedication of the local people. ‘I never saw people more reverent at prayer and at Holy Communion’, she noted. She remarked upon the significance of hat wearing for women at church. That is especially interesting for here was a ‘tradition’ still new and yet well-established. Woven hats were a legacy of the missionary emphasis upon respectable attire for worship in the islands. Local people took to it with alacrity as weaving was a skill spread throughout the Pacific, particularly where pandanus grew. Mats were woven to wear and to use as roofs and walls. Weaving created baskets, fish traps and sails. On Kiribati, warriors wore armour made from thickly woven cocoanut fibre. The tradition of making and wearing woven hats for church is still alive and well. In French Polynesia the headwear is called ‘Taupoo’ and in the Cook Islands it is ‘Rito’.

Hats were proper but the wearing of flowers were not. Neither were locals encouraged to ‘dance on their feet’, which I assume allowed some swaying to the rhythm while seated. Puzzled, and I suspect put-off, by ‘these puritanical restrictions’, Cara asked the visiting white missionary about their origin and purpose. He explained that ‘Samoans dressed in wreaths of flowers for their native dances, that these dances lasted all night, and developed into obscene and licentious orgies of an indescribable nature’. The restrictions were imposed by white missionaries on Samoa but then exported by local pastors to Ellice Island. Christianity had become so embedded within Polynesian society – the first London Missionary Society vessel arrived in Tahiti in 1797 – that islander on islander evangelism was widespread by the late 19th century.

The world for Ellice Islanders had expanded dramatically in the 50 years before Cara’s visit. Long part of a regional Pacific economy, by the end of the 19th century they were incorporated into a global culture of religion, science and trade. And yet the islanders embraced the people who turned up on their doorstep with apparent equanimity. They coined a word for Britannia, ‘Peritania’, and one for Sydney, ‘Sini’. There may have existed a sense of common humanity before the arrival of the missionaries but if so that was now expressed in terms of Empire, biology and the Christian god. ‘We, the people of Funafuti, are all very glad to see you here to-night at our sing-sing’, was the welcome given to Caroline, Edgeworth and others on one evening of song, ‘we are all friends, we are under the same Queen, we obey the same laws, and we worship the same God. There are black men and white men, and red men, but the heart and the blood are the same…’ Such an expression of equality cut across the hierarchies that were justifying colonisation across the world, scientific racism in particular.

Cara David seems to have received this openness with respect. Absent is any sense of superiority so often evidenced by drollness and irony in British commentaries. ‘Orphans and strangers were we when we landed at Funafuti, but in a very short time we had numerous official friends and quite a formidable array of relatives’. By that she was referring to the local custom of non-biological kinship, sometimes called ‘fictive kinship’ by anthropologists. A local woman called Tufaina became a ‘mother’ to the Englishwoman. In Cara’s words: ‘she told me that I was good, that she loved me, that she was my mother. I thanked her, said that I loved and respected her and was proud to be her daughter’. Cara herself became a mother to younger locals. She counted all the island women as her friends but singled out Peke ‘the trader’s handsome daughter’, Solonaima, and Tavaū ‘as the closest’.

Just as the British brought changes to Funafuti, island life seems to have changed Cara in the months she was there. When she, like the other loyal subjects, observed Queen Victoria’s Jubilee Day with a chorus of ‘God Save the Queen’, Cara did so, ‘to a tune of my own – I’d forgotten the right one’.

Cara went on to become President of the National Women’s Movement and a State Commissioner for the Girl Guides Movement.

More from the collection later…..

I am fortunate enough to be the CH Currey Fellow at the State Library of New South Wales this year. Charles Herbert Currey had dedicated his life to the teaching and writing of history and, in 1970, he left a large part of his estate to the Library to promote the study of history through original sources.

I put my hand up to look at the Library’s Pacific collection – in particular non-indigenous Australian writing about the surrounding islands in the period 1870-1970 when some began to think of their country as the natural regional power, the nation indeed acquired a colony and a protectorate in New Guinea, fought a war against the Japanese there and ultimately had to manage the transition of its dependency to independence – among other things. Since colonial times Australia’s relationship to its near Pacific neighbours has oscillated from intense interest to ignorance and amnesia. Over the past 20 years historians have been trying to recover what Warwick Anderson has eloquently called ‘our repressed Oceanic memories’. In 2016 Sean Dorney, the veteran reporter of Pacific affairs, criticised the collective forgetting of Australia’s history in Papua New Guinea in a paper to the Lowy Institute called ‘The Embarrassed Colonist’.

This is the first blog about my adventures in the State Library’s Pacific collection and beyond. Hopefully my own book on Australia-Pacific relations (due in 2020) will go some way to curing the amnesia.

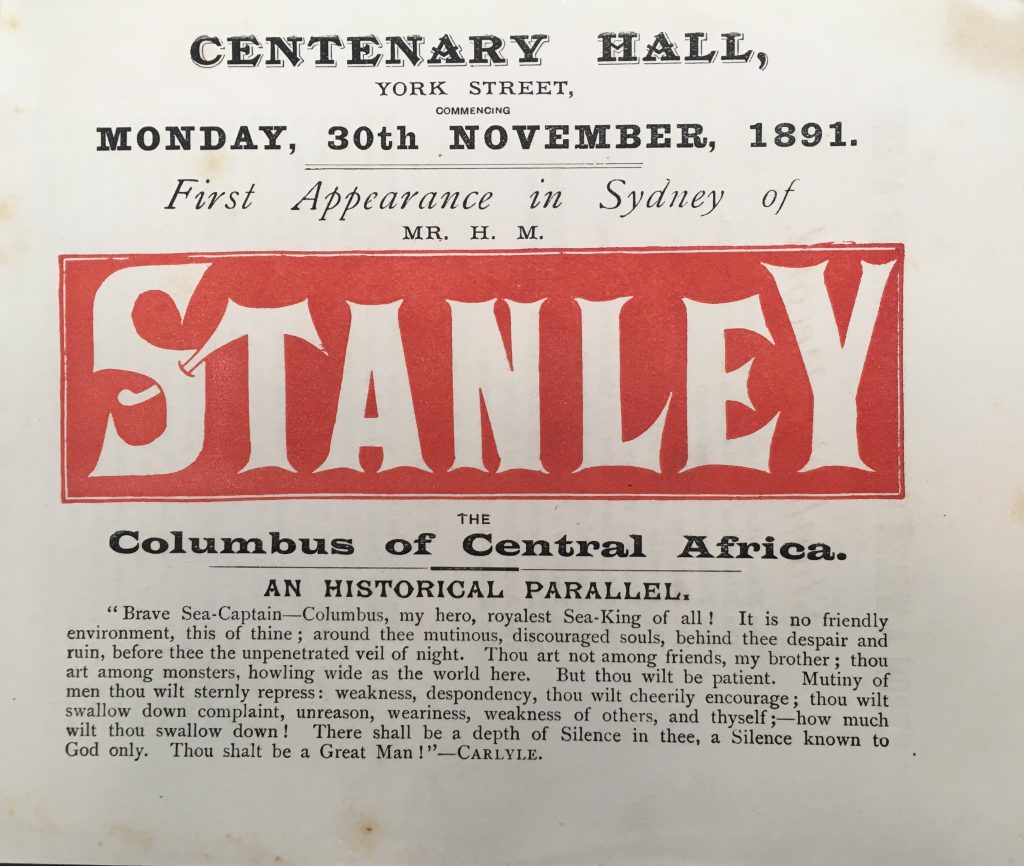

I have certainly struck a rich vein of material in the papers of the Royal Geographical Society of Australasia established in 1883. That was the heyday of exploration epitomised by the pith-helmeted adventure that became standard fare in ‘Boys’ Own’ journals. David Livingstone, of ‘Stanley and Livingstone’ and ‘Dr Livingstone I presume’ fame, had been elevated to the status of British national hero in 1774. Indeed, the Society’s papers include flyers advertising the ‘First Appearance in Sydney’ of Henry Stanley, ‘The Man who Found Livingstone’, on 30 November 1891. Europeans were heading into Africa, Asia and the Pacific in unprecedented numbers, to convert souls to Christianity (Livingstone was a missionary), discover natural wealth for exploitation, stake out imperial claims and study human diversity.

The Society’s first meeting to elect officer holders was on 29 May 1883. These were professionals, scientists, and businessmen – I have not yet come across a woman in their ranks. On 23 June its Honorary Secretary, French-born geographer Edmond La Meslée, addressed an audience of 750 with a talk on the short history of exploration in New Guinea – the ‘dark island’. There was still much to know so Meslée also outlined the goals and requirements of an expedition of further exploration. As to who would take part, Meslée suggested that the colonies could readily provide qualified surveyors, medical men and collectors for there was ‘no lack among us of men of the right stamp’.

It was Meslée’s justification for colonisation that is most interesting. For in this time of competitive imperialism and swirling theories of race, including those influenced by Social Darwinism, he criticised the ‘Anglo-Saxon’ race for its history of violence against ‘natives’ and spoke in terms of the rights of indigenous people. White people had gone wherever there was profit or gold and the outcome for local people was generally poor. The ‘total extinction’ of Tasmania’s Aborigines was cited as a case in point. But with the inexorability of that apparent law of nature, it was incumbent upon any future ‘colonial power’ in New Guinea to protect the ‘natives’ against abuse and exploitation – for ‘humanity’ ‘has its rights’. This surely was an incipient call for the protection of the human rights of indigenous people – though not clearly defined.

Meslée suggested setting up an ‘exploration committee’ to secure funding in the manner of the Royal Geographical Society’s African Exploration Fund of 1877. The colonial newspapers – and there were many regional publications by the 1883 – reported the speech and there followed a stream of unsolicited applications to the Society from eager participants across the continent. (See Sydney Morning Herald 23 June 1883 for a full account of Meslée’s speech)

It was all a bit premature. That funding target was around £5000 and required lobbying the various colonial governments and appealing to companies and the public. The Society quelled expectations of an imminent expedition but set about making it happen.

The general excitement is understandable for New Guinea was news in Australia. In February 1883 Sir Thomas McIlwraith, the Queensland Premier, had asked the Imperial Government to annex the island for Queensland to offset its occupation by Germany. When the British did not bother responding – an interesting indication of their attitude to colonial acquisition – McIlwraith sent his own man up there to raise a flag regardless. The British relented fearing chaos on the colonial periphery, and British New Guinea was created as a protectorate then a possession. It became known as Papua. By then Germany was already present north eastern half of the island. They called it Kaiser Wilhelm Land. Somewhat confusingly this was later known as New Guinea. The Papua New Guinea that exists today is an amalgam of both. The Dutch controlled the western half of the island, what became West Irian Jaya, now West New Guinea or West Papua and under a repressive Indonesian rule – such are the legacies of imperial carve ups.

The British flag went up in November 1884. The Geographical Society promptly suggested that its long-planned expedition could help establish the ‘exact boundary line of the English Protectorate over New Guinea’. It also committed itself to lobbying for the annexation of ‘the whole of New Guinea … to the British Crown’, although that would have meant dislodging the Germans. That didn’t happen but Australia – newly federated in 1901 – was given authority over British New Guinea in 1902. Administration began in 1906. When Britain went to war with Germany in August 1914, Australia’s first military action was expelling German forces – something that was accomplished with pent-up eagerness in September. Australia was given German New Guinea as a League of Nations mandated territory after World War One. Two administrations operated until Papua and New Guinea were formally united under one Australian office in 1949.

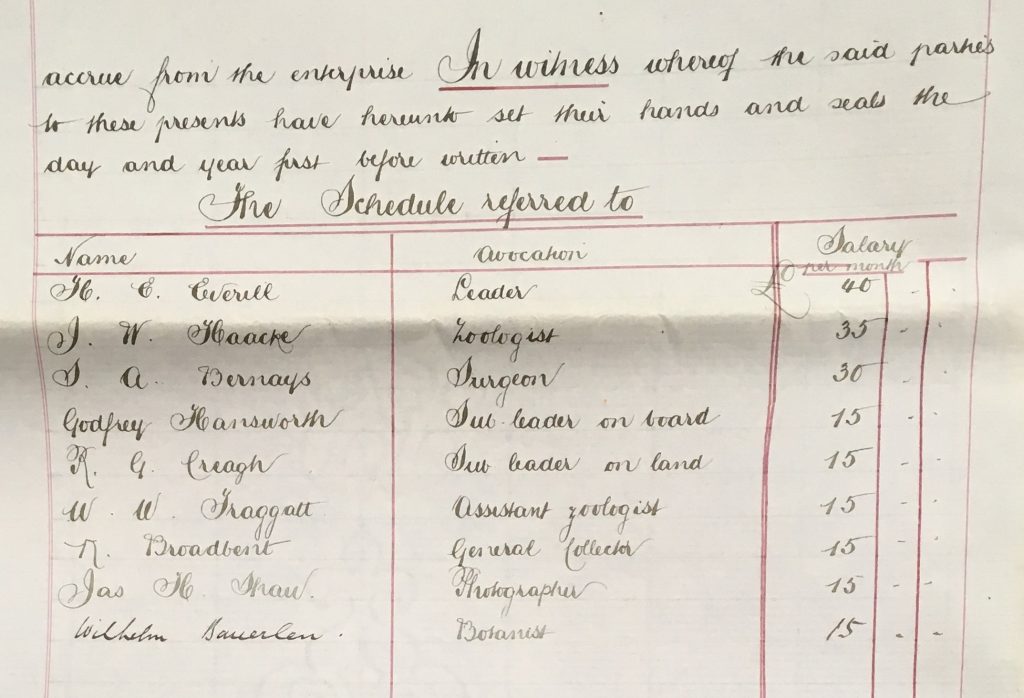

What makes the Geographical Society collection so rich, in my mind at least, is the minutiae of expedition organisation it contains. There is an insurance policy for the chartered steam launch covering ‘risk of capture and seizure by the Natives of New Guinea’. There are provisioning lists. It was estimated that a party of 12 Europeans would need 1000 lbs of corned beef, 1200 lbs of tinned beef and fish and a great deal of dried fruit, fish and preserved vegetables for an anticipated six months.

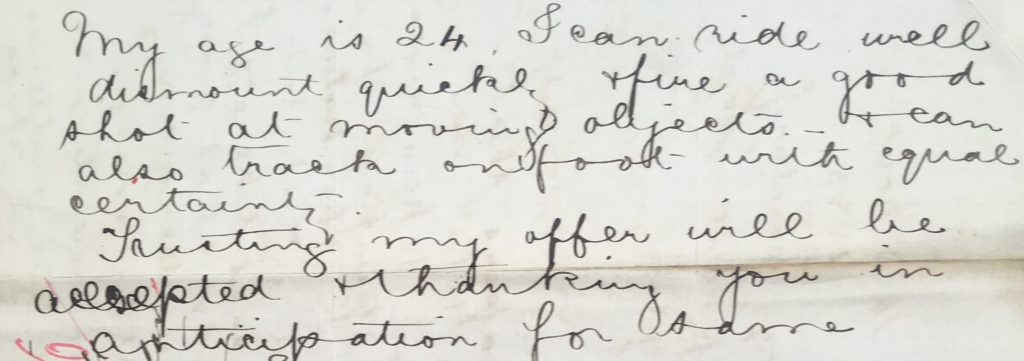

And then there are the letters of application which arrived shortly after the press covered Meslée’s speech. Significantly none that I read expressed or reflected upon the high-mindedness of the stated justification for exploration and colonisation – namely to make amends for the abuses of the past by establishing a benevolent colonial regime. Rather most show an eagerness for adventure or at least an interesting job. One hundred years of Australian colonisation may have turned out ‘men of the right stamp’ if that meant men who could survey the land, shoot, skin and preserve animals, survive in extremes and walk for miles. The self-description ‘bushman’ appeared several times. Many stressed their experience in dealing with ‘natives’. The need to follow orders was widely understood.

JH Shaw, from the Australian Museum had already spent two years in New Guinea and was part of an earlier exploratory expedition headed by veteran New Guinea trader Andrew Goldie who opened the first store on Port Moresby – an example perhaps of the inexorable expansion by ‘Anglo-Saxons’ that Meslée spoke of. His letter read: ‘I may be able to state that from early boyhood I have lived a roving & adventurous life both ashore and afloat… I might mention a practical intimacy with all classes of firearms’. Shaw was chosen.

A. Hammond Page was another veteran of ‘Goldies Collecting Camp’ in 1878. ‘I am not a taxidermist by trade’, he admitted, ‘but am an enthusiastic collector, a good shot, a fair preserver, can live and do well on the toughest fare’. Hammond Page did not make the final selection.

Neither did Arthur Esam, a young adventurer and professional artist from South Australia. He was already an experienced adventurer having accompanied surveying expeditions in Western Australia and travelled to Burke and Wills’ fateful Camp 65 on Cooper Creek to paint the famous carved tree in 1878.

There were many more unsuccessful applications. The Society clearly set a high bar, for another of the rejected hopefuls was Ernest Favenc who could claim to have led the first transcontinental expedition from Blackall to Port Darwin in 1878-79. ‘I am used to a tropical climate’, he wrote, ‘and used to dealing with natives, and could also I think command the services of equally experienced bushmen who have been my comrades before’. Favenc’s failure to secure a place on the New Guinea expedition gave him time to write the popular and influential History of Australian Exploration 1788-1888.

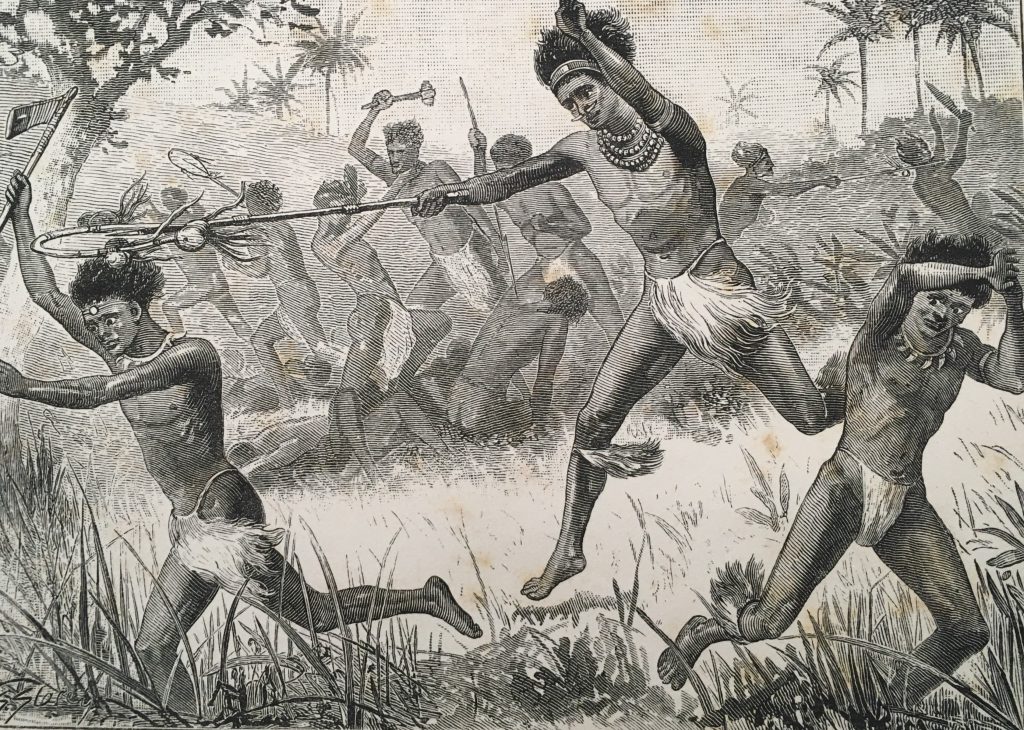

The party left for New Guinea in July 1885. Then in September there were rumours of a massacre up the Fly River. Telegrams and letters went back and forth until the story was disproved but not before the reports had broken in the press. They prompted one ex-Natal Mounted Police officer, Richard Searle, newly-arrived in the colony, to offer his services for a second expedition ‘for the purposes of punishing the natives concerned in the late massacres’. Thankfully that punitive excursion did not take place but Searle’s mentality of swift revenge is palpable and potentially lethal such was his set of martial skills transferred from one frontier to another.

And so the collection lays out the sweep of the colonising mindset, from the humane paternalism of Meslée, who acknowledged the people of New Guinea as humans with rights, to Searle’s eagerness for revenge for a massacre that did not occur. All attitudes of men of the ‘right’, and sometimes wrong, stamp left legacies in the post-colonial age.

More to follow…