The response of authorities to the recent awful shark attack off Tathra Beach on the NSW south coast could not have been more different to the vigilantism of the West Australian government after the spate of attacks on that side of the continent. In the west, protection afforded the endangered Great White Shark was set aside with the support of the conservative Federal Government so that that species could be killed, along with other types, by baited drum lines or shooting. People’s absolute right to swim unthreatened was deemed paramount and this underpinned the renewed right to kill normally protected sharks.

There was none of that in NSW. Not even a hunt for the predator itself – a fish which all agreed must have been large.

Neither did the public urge a pursuit. Instead there was a wave of grief and dignified expressions of sympathy for Christine Armstrong and her husband Rob, both regular ocean swimmers. Rob concluded that the extent of the support was less reflective of the manner of his wife’s death, than the esteem in which she was held.

It was a significant distinction because there are few fears for Australians as perennial as shark attack. Aboriginal people regarded the animals with trepidation even as they were incorporating them in creation stories. The sea-faring British were well aware of the fish before they colonised these coasts. There was already, quite literally, an unsavoury association between sharks and ‘man-eating’ among sailors when the Endeavour headed out to the Pacific in 1768, ultimately to sail up the Australian east coast. Then Joseph Banks suggested that the crew’s reluctance to eat stewed shark was founded on ‘some prejudice founded on the species sometimes eating human flesh’.

Awareness of the threat of attack in Australian waters developed in the first months of the colonisation of Sydney Harbour. A wobbegong, which continued fighting for life after it was caught in 1788, was described as ‘voracious’. The newcomers noted the fear sharks inspired among the Harbour clans who had lived with the creatures for generations.

Convicts and the guards were warned off swimming in the harbour – the beginning perhaps of a tradition of Australian ‘life-saving’ regulation.

Over the following two centuries some 228 people were killed by sharks (Taronga Conservation Society Shark Attack Files, http://taronga.org.au/animals-conservation/conservation-science/australian-shark-attack-file/latest-figures)

As a fear-driven hatred of sharks grew concurrently, countless thousands of the fish were killed. A lot were caught for food but many more for fun; and quite a few of those out of vengeance. Recreational fishing burgeoned from the end of the 19th century. Game fishing was glamorous by the 1930s when American writer Zane Grey visited these waters and caught sharks and other big fish. Radio and TV celebrity Bob Dyer continued the association between wealth and catching sharks in the post-war years. There was even a sense of noblesse oblige as the rich helped rid the oceans of malicious creatures.

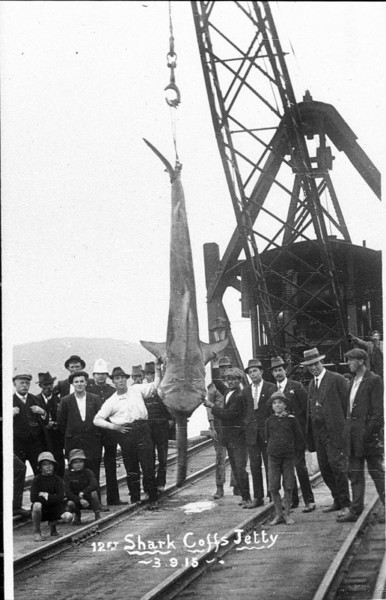

Photographs of slain sharks in this period share something with the grotesque photographs of lynching victims in the USA. Both typically feature a crowd around the cadaver, sometimes grinning, sometimes grim, but always sanctioning the debasement and killing of the monster among them.

It was recollections of this type of tableau vivant that novelist and conservationist Tim Winton evoked in his recent denunciation of the baiting of drum lines and by-passing of laws protective of sharks in his home State: ‘I remember enormous distended carcasses suspended from meat hooks and steel cables in jetties in Albany… Western Australia’. (Sydney Morning Herald 14 December 2013) Though admitting some attitudinal changes, Winton saw much that remained the same.

Winton’s anger prompted writer Richard King to characterise his pessimism as misanthropy. It ‘is important not to demote human beings from masters of the universe to spiteful monsters’. King’s attempt to understand the widespread protest against the Western Australian ‘shark cull’ was, itself, a strange piece. Though ultimately agreeing that we enter the sea at our own risk, King felt the need to dismiss the emotion of those criticising their government’s reaction to shark attack as part of a ‘cause celebre’, an example of ‘the politics of easy indignation’. (The Monthly, March 2014). ‘Precisely why this issue has gripped the collective imagination is a difficult question to answer’, he wrote. And indeed he didn’t answer it.

The shift in attitude to sharks has been quick. But so too was the change in our attitude to whales. Their dismembering was a tourist attraction when Winton was a boy in Albany in the 1960s. We had been hunting them mercilessly for 150 years before that. However within 20 years of Winton’s experience, Australians were helping to dislodge stranded whales along their coasts. There is now a near universal national revulsion at Japanese whaling in southern waters. Knowledge of the ecological disaster that whaling entailed has been joined with a moral disapproval at the cruelty of their slaughter. So, too, with sharks.

Perhaps, in Australia, our attitude to marine fauna follows with a lag that to land animals. Hunting is no way near as acceptable and widespread as it was the 1960s, let alone the 1860s when rambles routinely involved the shooting of anything that moved. We were creating terrestrial parks a century earlier than their marine equivalents.

The latter are still very much contested. But debate over marine parks in the NSW state elections of 2011 suggest that some are also beginning to question the sanctity of recreational fishing – long regarded as an almost sacred right among Australians, and the last widely popular form of killing wild animals.

As with the shark cull in Western Australia, the Federal Government has clearly indicated its willingness to roll back marine park protection. It will be interesting to see how the debate unfolds.

The sense of an unmitigated right to kill has underpinned our attitude to nature for centuries. Coupled with the means and propensity to completely destroy entire ecologies, it has been disastrous.

If a bit of humility or ‘indignation’ – however ‘easy’ – leads to a questioning of this, surely that can only be a good thing.