Follow my fellowship III: ‘The mountain cannot speak’

Visiting a place one intends to write about makes an immense difference. It really does. I spent three weeks in Papua New Guinea [PNG] in September trying to get a feel for the country that Australia ‘ruled’ as a colony from 1905 – that was Papua – and a territory from 1919, New Guinea. PNG came into being in 1949. The trip was background for my upcoming history of Australia and the Pacific. The CH Currey Fellowship from the State Library of New South Wales certainly helped to fund it; PNG is an expensive place to visit.

I was four days in Rabaul trying quickly to get a sense of the town which the Germans built in 1910 as the capital of their Pacific colony, the Australians took over in 1914 and made the centre of their League of Nations Mandate from 1919, the Japanese captured in January 1942 as the forward base of their Pacific campaign and the Australians reclaimed in 1945. What was left of old town after Allied bombing was destroyed 49 years later by a volcanic eruption. Four days was not long enough but I covered a lot of ground and had read up in preparation.

The papers of Kenneth Thomas, copied from the Pacific Manuscript Bureau collection and held at the State Library of New South Wales, describe the town encountered by a cadet patrol officer in 1927. The young Thomas headed straightaway to Rabaul’s ‘Chinatown’ area to be fitted out with his khakis from the tailor Chong Hing. He bought his helmet from Burns Philp, the Australian shipping and trading firm which dominated ‘Australia’s Pacific’ before the war, and for a time afterwards.

The Library also holds the original ‘War Diary’ of Jock Maclean who, as a planter, evacuated his family to Australia in late 1941 when news of war with Japan spread; ‘Many people were about, rushing from one place to another. Everyone seemed dazed’. His family farewelled, Maclean then escaped the Japanese invasion in January with a trek and boat journey to Buna, the very place where the Japanese would later land before the ‘Battle of Kokoda’. It is tempting to describe Maclean’s ordeal as extraordinary but, in 1942, it wasn’t.

The Australian writer Ian Townsend has told the awful story of the execution of 11-year-old Dickie Manson with his mother and her defacto partner at the hands of the Japanese in his book Line of Fire. The American historian Bruce Gamble wrote three books on wartime Rabaul, including Fortress Rabaul which I found really useful. It is also unusual to read an American take on an Australian story. Brett Evans wrote and presented the radio documentary ‘Last Letters’ which told of the Japanese mail drop of letters over Port Moresby written by prisoners captured in Rabaul. What might have been a rare act of humanitarianism by the Japanese turned out to be a more typical expression of cruelty. The prisoners were already dead.

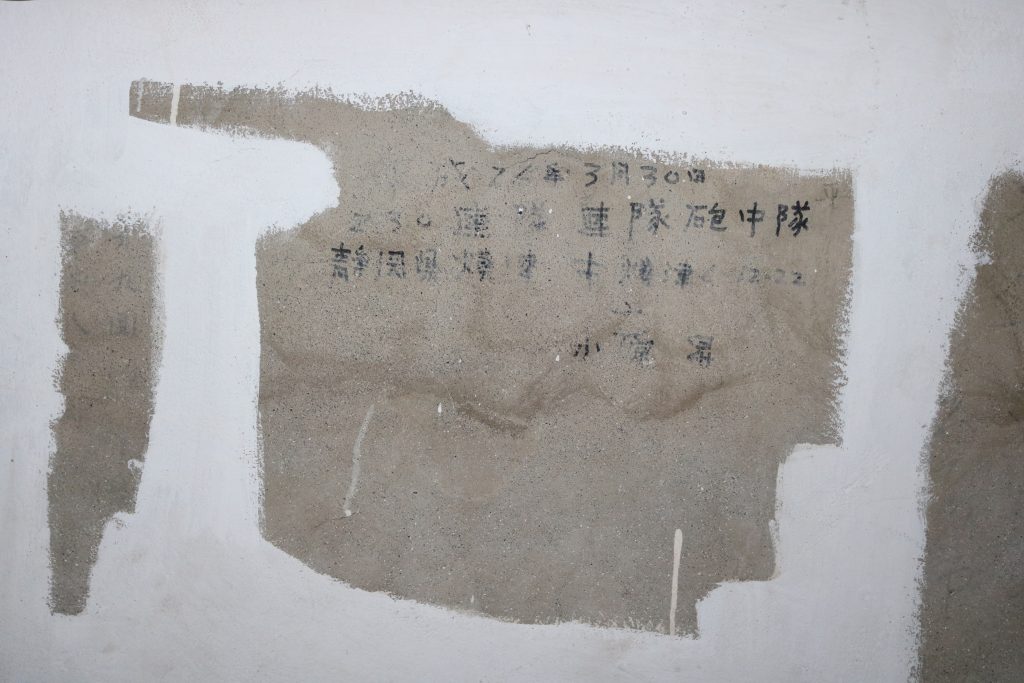

That was home work, but on the ground one really needs a good local guide to suggest places of interest and get to them, particularly if time is short. I am so grateful to the Rabaul Hotel, which survived the eruption, for their useful suggestions. I am so very appreciative of local historian Albert Koni who then took me to Japanese tunnels, airfields, wrecks, museums, execution sites and a submarine base. There I snorkelled along a reef drop off before entering two of five tunnels dug into the volcanic cliff face to store supplies for the subs. The last leg of our adventure had us crunching across the red and black beach of volcanic gravel towards the mountain that erupted and the site of Dickie Manson’s execution, a place identified by Albert after talking to a local man who learned Japanese during the war.

Albert Koni was born in Rabaul, the main centre of East New Britain. His parents were from the Sepik region on the mainland but he claims local Tolai identity by birthright and is recognised as Tolai by others. He trained and worked locally as a butcher and only came to history late in life. Albert takes tours with passengers from the cruise ships that occasionally visit. It must have taken some courage to make that career shift. Albert is deputy president of the local historical society which uses the old New Guinea Club as its headquarters and museum. The pre-war Club was racially exclusive, as were all of Rabaul’s places of entertainment during the Australian administration. I’m not sure if there is irony there but it is certainly poignant. Albert has never studied history formally but his knowledge is extensive. It is matched by his passion and his love for Australia, somewhere he has never visited. That one of his family was tortured by the Japanese has influenced that affection. But he also believes Australia brought modernity to New Britain, and that was a good thing. Albert is a proud Parramatta Eels supporter and wears the football team’s anniversary cap to prove it.

The story of Rabaul during World War Two is Albert’s special interest. He is quite right in believing this is barely known let alone understood in Australia. The battle of Kokoda has been elevated in the Australian collective consciousness so that it rivals, almost, the mythic status of Gallipoli and the Anzacs. But despite the books and broadcasts few who don’t have personal connections with Rabaul, family who served there for instance, know about the tragic story of the abandonment of the 2/22 Infantry Battalion who defended the town along with a few ineffective aircraft and other defence personnel. This was one of the island ramparts that Prime Minister Billy Hughes fought for after World War One. It was, consequently, given to Australia as a Mandated to manage and develop ethically. The men at Rabaul were an ‘advanced observation line’ on that rampart. In the event of an invasion they were to ‘make the enemy fight for [that] line’ in the words of the Australian Chiefs of Staff. But even before the outbreak of war those men knew that the garrison could not withstand the scale of attack that the Japanese could mount. They were right. The defenders of Rabaul were doomed from the start. More than 100 were bayonetted to death by the Japanese with their hands tied behind their backs. A similar number of Tolai people were taken to Papua as forced labour on the Kokoda campaign. I suspect few of them returned.

I asked Albert why he was so interested in history and he came back with something quite poetic and unexpected: ‘The mountain cannot speak’. It is up to people to do the talking, he said. And then cryptically ‘History will sustain you’. The puzzle that is our past will never, of course, be completely reconstructed or understood. But trying to put some of the puzzle pieces together sustains me too.

Thanks Albert.