It being nearly Christmas, some may be considering things loftier than the usual splurge on gifts and food. My mind was turned to religious architecture again during a recent wander around Armidale in northern New South Wales – a country centre with two fine cathedrals (Anglican and Catholic) and a very handsome Presbyterian Church adjacent to the retail centre.

I often tell those who come on my guided walks around North Sydney that architecture provides the most accessible way of comprehending the material culture of past generations. Unlike clothing, cars or other forms of technology, the structures of the past are still all about us.

Few buildings wear the ideological intent of the architect or owner more clearly than places of worship and their associated structures. These were literally built to express and evoke religious sentiment. And what I find especially fascinating is that, despite the apparent immutability of the truths presented in them, buildings erected by the various Christian churches in Australia reflect changing architectural fashion and thought just as non-sacred structures do.

Gothic architecture, in its various forms, was the dominant mode of sacred expression in this country through the 19th century and the first half of the twentieth. It is not surprising given that the consolidation of British occupation of the Australian colonies coincided with the revival of the Gothic in the ‘mother country’. Americans, by contrast, were far more willing to erect a church that looked like a Greek or Roman temple, something that would have appalled John Ruskin for whom classicism was synonymous with paganism.

The spiritual message of much Gothic architecture is clear. Cathedral spires and pinnacles reach for the heavens. Even in their absence the pointed arch window directs one’s gaze, and hopefully thoughts, upwards. Then, of course, in Catholic and some Anglican churches there is the obvious iconography apparent in statues and stained glass windows.

All this is very apparent with St Mary and Joseph’s Catholic Cathedral in Armidale. It was designed in 1910-11 by the firm Sherrin and Hennessey who did a huge amount of work for the Catholic Church at the time. Heavenly thoughts are conveyed to all who enter or pass by with the spire, pinnacles and pantheon of saints.

The Cathedral is built of brick rather than stone, as was the case with many Federation-era Gothic churches. In this instance the construction also shows off the characteristic local light and dark bricks and the polychromatic brickwork of the prolific local builder, GF Nott. St Mary and Joseph’s looks like it belongs in Armidale because of this localism.

The extravagant expression of Gothicism was pared back during the first half of the 20th century by the impact of Modernism, which celebrated mass production and tended to eschew ornamentation. Accordingly the celebration of the craft of the carpenter, bricklayer, and mason, so apparent in earlier Gothic structures, was muted and then lost altogether.

This move to austerity is so apparent in the ‘Cathedral Hall’ that was built by Armidale’s Catholics near the sublime structure from which it gets its name. It is clearly a building that has been designed rather than simply erected as a functional shelter. The Gothic ancestry is referenced by the stylised battlements on the bay front. The decision to leave the grey concrete render unpainted seems to be part of the original intent of the architect or builder. There is a grimness about it that may reflect the impact of the Great Depression, just past when the place was built. Possibly cost was an issue. To me it also expresses an age when totalitarian ideas were in conflict with democracy and the Catholic Church was trying to find its place within this turmoil. But was arrival at the Cathedral Hall meant to uplift and express hope in the future through its modernity? Or was the bleakness an attempt to cower a congregation and secure their allegiance? Either way, for such as small building, it is amazingly affecting.

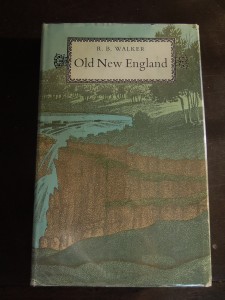

At the friendly end is Boobooks in Armidale itself. I visited their new premises the other week fired up with a need to find out more about local history because of a couple of drives through the surrounding grazing land that left me breathless with its beauty (see my previous blog-post).

At the friendly end is Boobooks in Armidale itself. I visited their new premises the other week fired up with a need to find out more about local history because of a couple of drives through the surrounding grazing land that left me breathless with its beauty (see my previous blog-post).

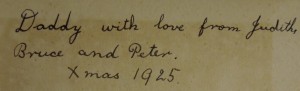

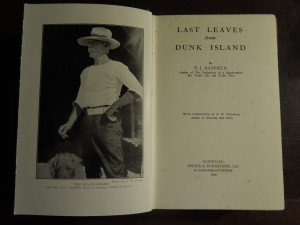

e ‘1925’ means the gift was likely prompted by the family’s recent cruise north to SE Asia, taken as a last attempt to improve her mother’s health. Ethel Wright died the following year and the young Judith was devastated. Last Leaves is double the treasure because of its provenance.

e ‘1925’ means the gift was likely prompted by the family’s recent cruise north to SE Asia, taken as a last attempt to improve her mother’s health. Ethel Wright died the following year and the young Judith was devastated. Last Leaves is double the treasure because of its provenance.