It is not easy finding good second hand bookshops in regional areas – at least not in my recent experience in NSW. For me an indicator of something special is the range of local history carried – books and monographs that are specific to the area and that one might not find elsewhere.

Armidale and surrounds are an exception; almost certainly because the town has a University of long standing and high repute – the University of New England – and there have long been good researchers and writers in the Armidale and District Historical Society.

There are two good bookshops there. The first, Burnett’s Books, has been in the beautiful little town of Uralla (20 minutes south of Armidale) for at least a decade. That place is worth a visit in its own right because of the new boutique brewery, McCrossins Mill Local Museum and the Uralla Wool Room (the latter is owned by my sister – so I should add a disclaimer).

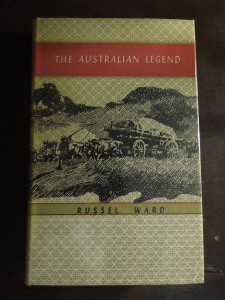

My nicest find in Burnett’s was a 1960 edition of The Australian Legend signed by the author. Russel Ward, of course, taught at the University of New England and completed that foundational study of Australian identity there in 1957/1958 when it was published. So my volume is not quite a 1st Edition but it’s signature and location give it a very nice provenance and proximity to the author.

Another discovery had both local associations and relevance to the Sydney Harbour history I was writing at the time. That was Nancy Keesing’s Garden Island People in mint condition published by the Wentworth Press in 1975 but signed by the author and dedicated to Russel Ward in 1983.

That trawl also produced Laurence Le Guay’s Sydney Harbour, a photographic work from 1966 (the year I arrived in Sydney Harbour as a boy in a boat!) with a great preface by Kenneth Slessor.

Burnett’s has some gems but don’t go there expecting conversation. Despite my many purchases I rarely get a hello – it is at the ‘Black Books’ end of the spectrum for those familiar with that comedy series. At the friendly end is Boobooks in Armidale itself. I visited their new premises the other week fired up with a need to find out more about local history because of a couple of drives through the surrounding grazing land that left me breathless with its beauty (see my previous blog-post).

At the friendly end is Boobooks in Armidale itself. I visited their new premises the other week fired up with a need to find out more about local history because of a couple of drives through the surrounding grazing land that left me breathless with its beauty (see my previous blog-post).

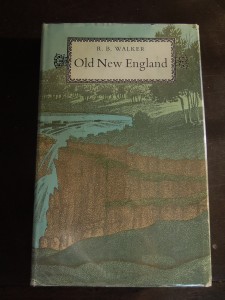

It was a fruitful visit. Sitting on top of a new acquisitions table was RB Walker’s Old New England – a 1st Edition from 1966 by Sydney University Press in mint condition. And a great read.

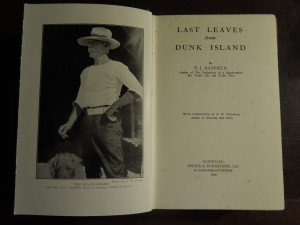

Down in the local history section was another 1st Edition; this one EJ Banfield’s Last Leaves from Dunk Island. There is very little literature about the Australian coast before the post-war period and the poetry of John Blight and a few others. Robert Drewe and Tim Winton were pioneers of a genre as late as the 1980s.

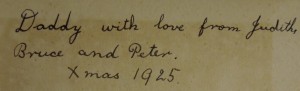

The temptation to get this volume because of my interest in the coast increased when I saw in a child’s hand the dedication to ‘Daddy’ followed by the names Judith, Bruce and Peter. There, too, was the original Armidale bookseller’s stamp.

The Wrights were a prominent local family. A quick consultation of the online Australian Dictionary of Biography confirmed my hunch that this was Judith Wright’s Christmas present to her father – probably chosen by her and on behalf of her younger brothers. The dat e ‘1925’ means the gift was likely prompted by the family’s recent cruise north to SE Asia, taken as a last attempt to improve her mother’s health. Ethel Wright died the following year and the young Judith was devastated. Last Leaves is double the treasure because of its provenance.

e ‘1925’ means the gift was likely prompted by the family’s recent cruise north to SE Asia, taken as a last attempt to improve her mother’s health. Ethel Wright died the following year and the young Judith was devastated. Last Leaves is double the treasure because of its provenance.