Two things have got me thinking again about the meaning of trees. The first was the trip to New England NSW I have mentioned in the previous two blogs. There trees are hard to ignore. They stand in stark lines across sheep pastures. They clump around dwellings. They form avenues, glow with autumn colour or dot the grassland as contorted grey trunks, ringbarked years ago or killed by die-back.

The second was re-reading Michael Pembroke’s really beautiful book Trees of History and Romance: Essays from a Mount Wilson Garden, in which the horticulture and cultural history of 21 types of exotic trees – those that grow in the author’s mountain garden – are outlined.

My postgraduate work on public parks and the symbolism of flora, twenty or so years ago, made me very aware of the historical ambivalence of many non-indigenous Australians to the vegetation of the country they took from the first people. ‘The invaders hated trees’ was WK Hancock’s unequivocal summation. Writing in 1930, he was responding to more than a century of de-afforestation. By then, the Big Scrub, that once covered 75,000 hectares around the northern rivers of NSW, had all but disappeared. Such was its size and so sanguine were newcomers that they estimated the forest would last 600 years. Hancock saw it all as the hollow triumph of the ‘greed’ and ‘ignorance’ of a ‘transplanted’ people. (WK Hancock, Australia, [1930], 1945, pp.30-33)

Of course the ‘transplanted’ did not hate all trees. In time, they actually came to celebrate the endemic flora. The golden wattle, for instance, would be embraced as a symbol of a nation – albeit a golden-haired, white one. Painter Hans Heysen and photographer Harold Cazneaux both elevated the maligned Eucalypt to the status of icon emblematic of the tenacious pioneer.

And the ‘transplanted’ people brought with them attitudes to trees that were deeply ‘rooted’ (the puns are telling and intentional) in British and wider European culture. They transplanted exotic species out of affection and practical familiarity.

It is interesting to wonder then what prompted the Dangar family, owners of Gostwyck sheep station on the New England plateau, to plant 200 English Elm trees (Ulmus procera) to create a grand avenue that would impress visitors coming to their big home. They were almost certainly aware of the use of Elms on coffins and ships’ hulls. But more so through English verse and painting, the Elm was synonymous with the working countryside – an association that a landed family of ‘improvers’ in ‘New England’ would be keen to promote. The Elms were planted sometime after the family felt it had consolidated its holding in the wake of the 1861 Selection Act which threatened to break up the vast properties taken up by squatters in earlier years. Gostwyck was established in 1836.

Elsewhere on the plateau there are stands of Radiata Pine (Pinus radiata) – huge trees at least 100 years old planted obviously as wind-breaks in pastures and around dwellings because their needles so effectively block moving air. These are North American trees but in the England of the late 18th and 19th centuries, conifers were increasingly planted on estates because they could flourish in the thin soil of moors that were being enclosed and thereby acquired by the landed. They were, then, widely known among the newcomers and were as emblematic as the Elm or Oak. In Australia, also, the shape and colouring of the pine was easily distinguished from that of the native flora. I think they must also have served as landmarks for those returning to home after working in the bush or pasture.

So when I see a stand of Pines, as opposed to a wind-breaking line, I wonder whether they once enclosed a home. Their presence in such formations is so clearly part of a cultural landscape. Like Gostwyck’s avenue of Elms, these Pines are evidence of the shaping intent of newcomers. But where the former speak of the permanence of the occupiers, empty Pine groves indicate their departure. Sometimes those stories can be recovered, often we can only imagine.

At the friendly end is Boobooks in Armidale itself. I visited their new premises the other week fired up with a need to find out more about local history because of a couple of drives through the surrounding grazing land that left me breathless with its beauty (see my previous blog-post).

At the friendly end is Boobooks in Armidale itself. I visited their new premises the other week fired up with a need to find out more about local history because of a couple of drives through the surrounding grazing land that left me breathless with its beauty (see my previous blog-post).

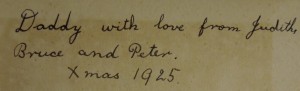

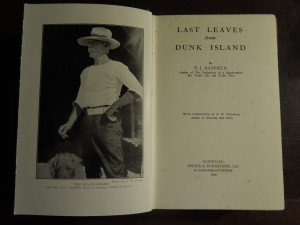

e ‘1925’ means the gift was likely prompted by the family’s recent cruise north to SE Asia, taken as a last attempt to improve her mother’s health. Ethel Wright died the following year and the young Judith was devastated. Last Leaves is double the treasure because of its provenance.

e ‘1925’ means the gift was likely prompted by the family’s recent cruise north to SE Asia, taken as a last attempt to improve her mother’s health. Ethel Wright died the following year and the young Judith was devastated. Last Leaves is double the treasure because of its provenance.