I am fortunate enough to be the CH Currey Fellow at the State Library of New South Wales this year. Charles Herbert Currey had dedicated his life to the teaching and writing of history and, in 1970, he left a large part of his estate to the Library to promote the study of history through original sources.

I put my hand up to look at the Library’s Pacific collection – in particular non-indigenous Australian writing about the surrounding islands in the period 1870-1970 when some began to think of their country as the natural regional power, the nation indeed acquired a colony and a protectorate in New Guinea, fought a war against the Japanese there and ultimately had to manage the transition of its dependency to independence – among other things. Since colonial times Australia’s relationship to its near Pacific neighbours has oscillated from intense interest to ignorance and amnesia. Over the past 20 years historians have been trying to recover what Warwick Anderson has eloquently called ‘our repressed Oceanic memories’. In 2016 Sean Dorney, the veteran reporter of Pacific affairs, criticised the collective forgetting of Australia’s history in Papua New Guinea in a paper to the Lowy Institute called ‘The Embarrassed Colonist’.

This is the first blog about my adventures in the State Library’s Pacific collection and beyond. Hopefully my own book on Australia-Pacific relations (due in 2020) will go some way to curing the amnesia.

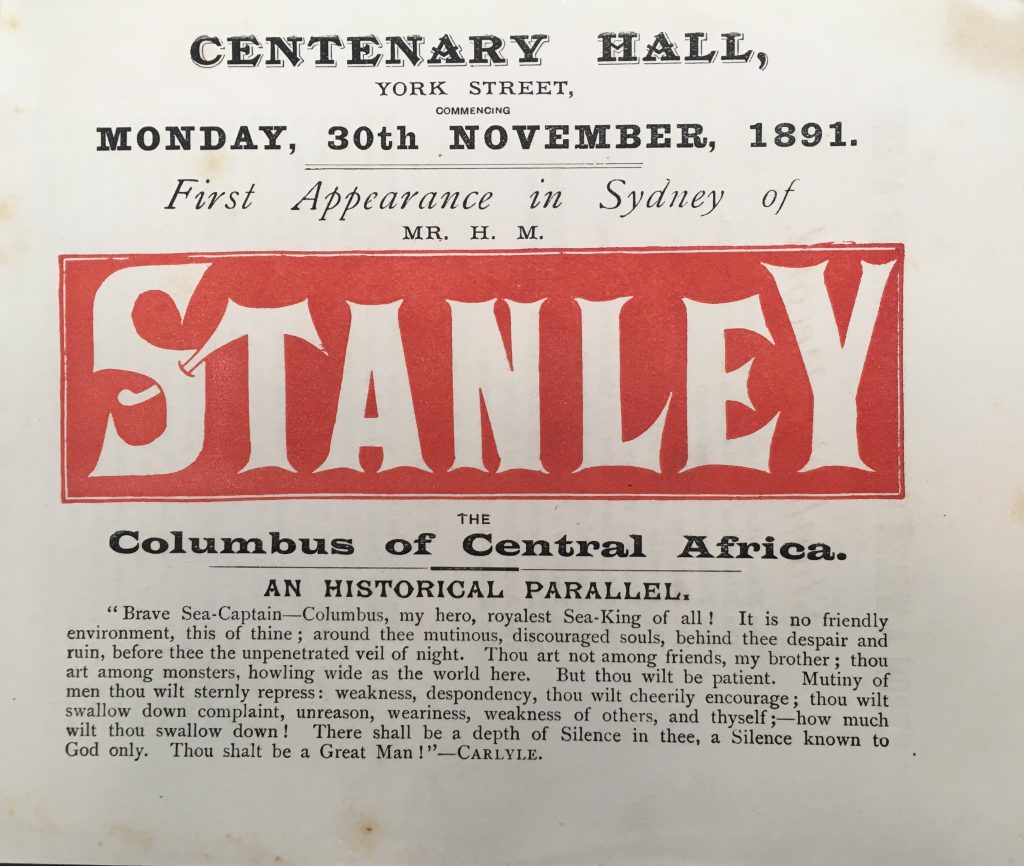

I have certainly struck a rich vein of material in the papers of the Royal Geographical Society of Australasia established in 1883. That was the heyday of exploration epitomised by the pith-helmeted adventure that became standard fare in ‘Boys’ Own’ journals. David Livingstone, of ‘Stanley and Livingstone’ and ‘Dr Livingstone I presume’ fame, had been elevated to the status of British national hero in 1774. Indeed, the Society’s papers include flyers advertising the ‘First Appearance in Sydney’ of Henry Stanley, ‘The Man who Found Livingstone’, on 30 November 1891. Europeans were heading into Africa, Asia and the Pacific in unprecedented numbers, to convert souls to Christianity (Livingstone was a missionary), discover natural wealth for exploitation, stake out imperial claims and study human diversity.

The Society’s first meeting to elect officer holders was on 29 May 1883. These were professionals, scientists, and businessmen – I have not yet come across a woman in their ranks. On 23 June its Honorary Secretary, French-born geographer Edmond La Meslée, addressed an audience of 750 with a talk on the short history of exploration in New Guinea – the ‘dark island’. There was still much to know so Meslée also outlined the goals and requirements of an expedition of further exploration. As to who would take part, Meslée suggested that the colonies could readily provide qualified surveyors, medical men and collectors for there was ‘no lack among us of men of the right stamp’.

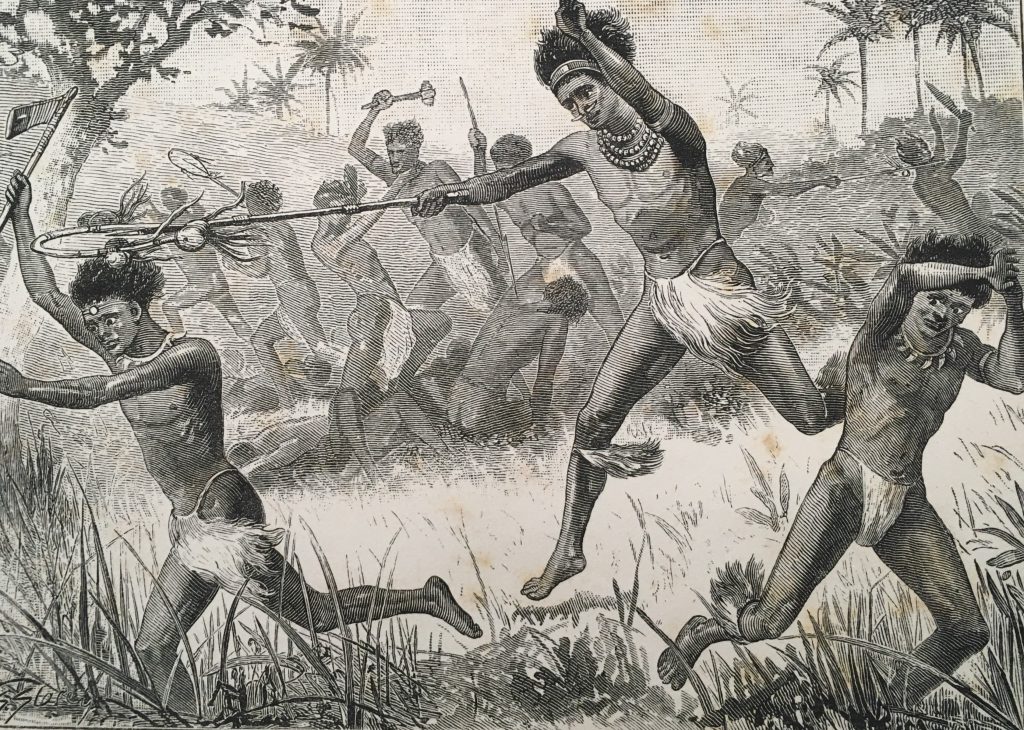

It was Meslée’s justification for colonisation that is most interesting. For in this time of competitive imperialism and swirling theories of race, including those influenced by Social Darwinism, he criticised the ‘Anglo-Saxon’ race for its history of violence against ‘natives’ and spoke in terms of the rights of indigenous people. White people had gone wherever there was profit or gold and the outcome for local people was generally poor. The ‘total extinction’ of Tasmania’s Aborigines was cited as a case in point. But with the inexorability of that apparent law of nature, it was incumbent upon any future ‘colonial power’ in New Guinea to protect the ‘natives’ against abuse and exploitation – for ‘humanity’ ‘has its rights’. This surely was an incipient call for the protection of the human rights of indigenous people – though not clearly defined.

Meslée suggested setting up an ‘exploration committee’ to secure funding in the manner of the Royal Geographical Society’s African Exploration Fund of 1877. The colonial newspapers – and there were many regional publications by the 1883 – reported the speech and there followed a stream of unsolicited applications to the Society from eager participants across the continent. (See Sydney Morning Herald 23 June 1883 for a full account of Meslée’s speech)

It was all a bit premature. That funding target was around £5000 and required lobbying the various colonial governments and appealing to companies and the public. The Society quelled expectations of an imminent expedition but set about making it happen.

The general excitement is understandable for New Guinea was news in Australia. In February 1883 Sir Thomas McIlwraith, the Queensland Premier, had asked the Imperial Government to annex the island for Queensland to offset its occupation by Germany. When the British did not bother responding – an interesting indication of their attitude to colonial acquisition – McIlwraith sent his own man up there to raise a flag regardless. The British relented fearing chaos on the colonial periphery, and British New Guinea was created as a protectorate then a possession. It became known as Papua. By then Germany was already present north eastern half of the island. They called it Kaiser Wilhelm Land. Somewhat confusingly this was later known as New Guinea. The Papua New Guinea that exists today is an amalgam of both. The Dutch controlled the western half of the island, what became West Irian Jaya, now West New Guinea or West Papua and under a repressive Indonesian rule – such are the legacies of imperial carve ups.

The British flag went up in November 1884. The Geographical Society promptly suggested that its long-planned expedition could help establish the ‘exact boundary line of the English Protectorate over New Guinea’. It also committed itself to lobbying for the annexation of ‘the whole of New Guinea … to the British Crown’, although that would have meant dislodging the Germans. That didn’t happen but Australia – newly federated in 1901 – was given authority over British New Guinea in 1902. Administration began in 1906. When Britain went to war with Germany in August 1914, Australia’s first military action was expelling German forces – something that was accomplished with pent-up eagerness in September. Australia was given German New Guinea as a League of Nations mandated territory after World War One. Two administrations operated until Papua and New Guinea were formally united under one Australian office in 1949.

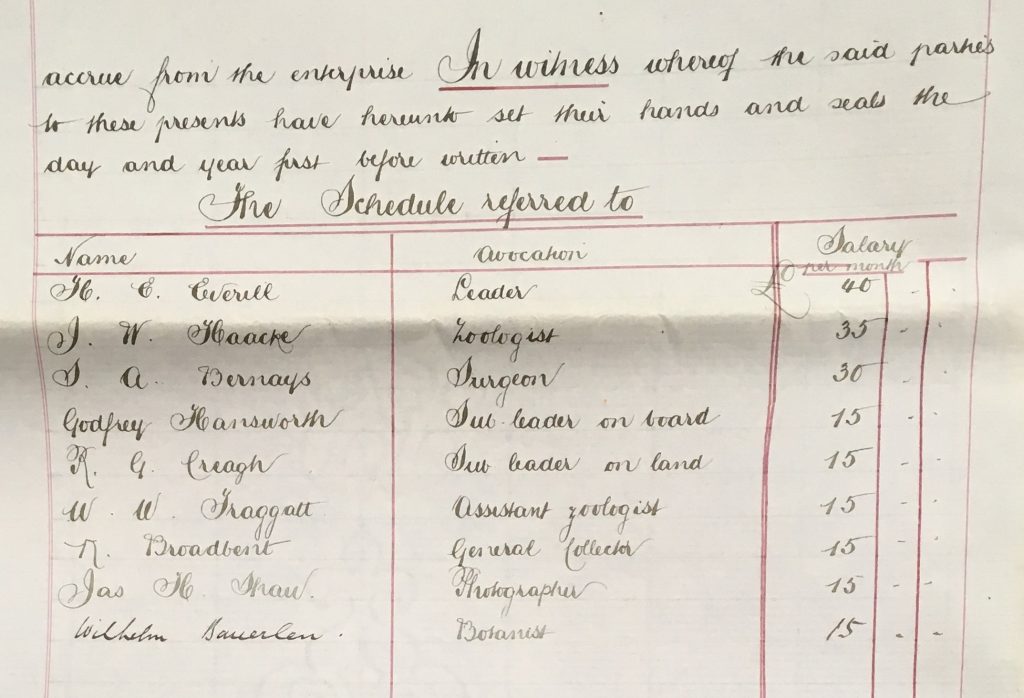

What makes the Geographical Society collection so rich, in my mind at least, is the minutiae of expedition organisation it contains. There is an insurance policy for the chartered steam launch covering ‘risk of capture and seizure by the Natives of New Guinea’. There are provisioning lists. It was estimated that a party of 12 Europeans would need 1000 lbs of corned beef, 1200 lbs of tinned beef and fish and a great deal of dried fruit, fish and preserved vegetables for an anticipated six months.

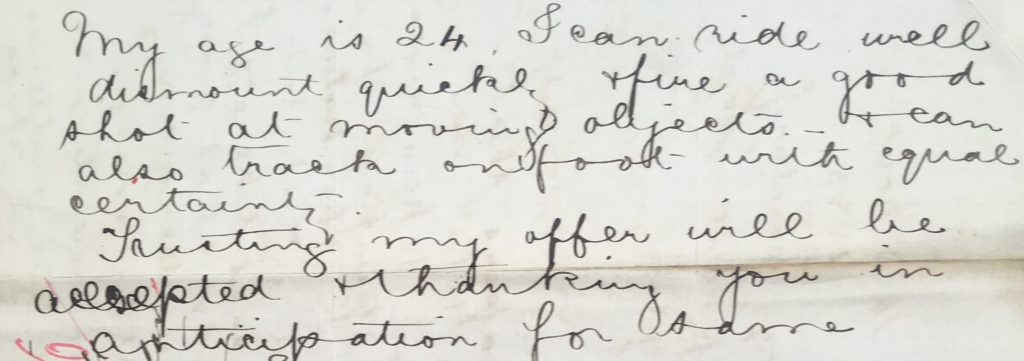

And then there are the letters of application which arrived shortly after the press covered Meslée’s speech. Significantly none that I read expressed or reflected upon the high-mindedness of the stated justification for exploration and colonisation – namely to make amends for the abuses of the past by establishing a benevolent colonial regime. Rather most show an eagerness for adventure or at least an interesting job. One hundred years of Australian colonisation may have turned out ‘men of the right stamp’ if that meant men who could survey the land, shoot, skin and preserve animals, survive in extremes and walk for miles. The self-description ‘bushman’ appeared several times. Many stressed their experience in dealing with ‘natives’. The need to follow orders was widely understood.

JH Shaw, from the Australian Museum had already spent two years in New Guinea and was part of an earlier exploratory expedition headed by veteran New Guinea trader Andrew Goldie who opened the first store on Port Moresby – an example perhaps of the inexorable expansion by ‘Anglo-Saxons’ that Meslée spoke of. His letter read: ‘I may be able to state that from early boyhood I have lived a roving & adventurous life both ashore and afloat… I might mention a practical intimacy with all classes of firearms’. Shaw was chosen.

A. Hammond Page was another veteran of ‘Goldies Collecting Camp’ in 1878. ‘I am not a taxidermist by trade’, he admitted, ‘but am an enthusiastic collector, a good shot, a fair preserver, can live and do well on the toughest fare’. Hammond Page did not make the final selection.

Neither did Arthur Esam, a young adventurer and professional artist from South Australia. He was already an experienced adventurer having accompanied surveying expeditions in Western Australia and travelled to Burke and Wills’ fateful Camp 65 on Cooper Creek to paint the famous carved tree in 1878.

There were many more unsuccessful applications. The Society clearly set a high bar, for another of the rejected hopefuls was Ernest Favenc who could claim to have led the first transcontinental expedition from Blackall to Port Darwin in 1878-79. ‘I am used to a tropical climate’, he wrote, ‘and used to dealing with natives, and could also I think command the services of equally experienced bushmen who have been my comrades before’. Favenc’s failure to secure a place on the New Guinea expedition gave him time to write the popular and influential History of Australian Exploration 1788-1888.

The party left for New Guinea in July 1885. Then in September there were rumours of a massacre up the Fly River. Telegrams and letters went back and forth until the story was disproved but not before the reports had broken in the press. They prompted one ex-Natal Mounted Police officer, Richard Searle, newly-arrived in the colony, to offer his services for a second expedition ‘for the purposes of punishing the natives concerned in the late massacres’. Thankfully that punitive excursion did not take place but Searle’s mentality of swift revenge is palpable and potentially lethal such was his set of martial skills transferred from one frontier to another.

And so the collection lays out the sweep of the colonising mindset, from the humane paternalism of Meslée, who acknowledged the people of New Guinea as humans with rights, to Searle’s eagerness for revenge for a massacre that did not occur. All attitudes of men of the ‘right’, and sometimes wrong, stamp left legacies in the post-colonial age.

More to follow…