My previous blog got its title from the call for an expedition to New Guinea by the Honorary Secretary of the newly-established Geographical Society of Australasia in 1883. Edmond La Meslée spoke confidently of finding ‘men of the right stamp’ to head off in the cause of benevolent colonialism. As I work my way through the many books published about the Pacific in the late 19th century its proving hard to find a woman’s voice among all those ‘good men’ who plied the Pacific doing their patriotic duty, saving souls, furthering science or making money… and then writing about it.

Caroline ‘Cara’ David’s account of her visit to Funafuti in the Ellice Islands (today’s Tuvalu) in 1897 is not only unusual because of its female perspective, it is remarkably candid, down-to-earth and free of the worthy pomposity and superiority that characterises so much Victorian travel writing. One gets a sense of that from the title: Funafuti or three months on a coral island: An unscientific account of a Scientific Expedition.

Mrs Edgeworth David, as her name appears in the book, was the wife of the renowned geologist Tannant William Edgeworth David, better known as Edgeworth David. There is a building at my old alma mater, Sydney University, named after him. He was Professor of Geology there from 1891. As was the Australian custom until living memory, married women of social standing were typically referred to by their husband’s entire name – for he was the one who established the standing. So it was with Cara despite her education and profession as a teacher.

Edgeworth David’s intention on Funafuti was to investigate Charles Darwin’s theory of the creation of coral reefs. His Galapagos Islands epiphanies are well-known today, but Darwin’s coral theory is a relatively little discussed part of the famous trans-Pacific voyage in the Beagle. Yet it was a significant step in the gestation of the theory of evolution. Darwin’s 1842 work On the Structure and Distribution of Coral Reefs anticipated the more famous On the Origin of Species published in 1859 by describing the evolution of ecosystems over time, a concept that differed clearly from Biblical creationism in which all life was perfectly made by God in seven days. It also challenged the ‘catastrophism’, the theories of sudden change, expounded by others who were struggling to explain the evidence of apparently displaced rocks, and the fossil remains of creatures long gone, within a paradigm which respected Christian precepts.

I’m guessing Cara and Edgeworth had a close and respectful relationship. As she wrote: ‘my husband said he was going, and politely hinted that I should be an idiot not to go with him. After that there was nothing for me to say’. It was not just, or even, wifely devotion that convinced Caroline to go: Funafuti was, she thought, ‘so intensely interesting’.

British-born Cara and Edgeworth had met on their passage to Australia in 1882, she to take up a post as the Principal of Hurlstone Training College for women teachers and he as the colony’s Assistant Geological Surveyor. They were married in 1885. Caroline’s college was near Ashfield in Sydney’s expanding western suburbs. Edgeworth spent most of his first two years in the field around New England in northern New South Wales. Separation might, therefore, have delayed the wedding.

Here is Cara’s description of the travel homework she undertook with Edgeworth: ‘We noticed that no two atlases agreed to the exact position of the Ellice Group… The map labelled the islands British by putting a pink line under the name. Under our own flag, anyhow! And if the black people kill and eat us, we shall be avenged! Unutterable comfort in that thought! We found afterwards that the Ellice Islanders hadn’t the faintest desire to kill and eat us; on the contrary, they were quite as civilised as most white folk.’ My reading of those remarks suggests a woman poking gentle fun at the authority of Empire, the associated certainty of cartographic knowledge and the assumptions about primitive ‘otherness’ that pervaded Pacific writing throughout the century.

The Davids chugged along for eight days in the steamer that took them from Sydney to Fiji. A smaller vessel delivered the party to the Ellice Islands. Having recovered from the sea-sickness endured on that last leg between Suva and Funafuti, Cara set about domestic duties and taking note of the locals. Personal space and seclusion were things she immediately recognised as one feature of British society not shared in the Ellice Islands. Under the scrutiny of the islanders, she craved ‘the privacy of the poorest Englishman’s cottage’.

With Edgeworth out exploring drill sites for the coral core samples, Cara cleaned their allocated hut and arranged it as best she could along the lines of the hygienic, compartmentalised Anglo-Australian home: ‘I spread a layer of clean white coral pebbles [on the floor], and over them again a layer of rough palm-leaf mats, and over all three good pandanus leaf-mats… Then I placed the sleeping-stretchers at one end of the hut and close by them arranged toilet requisites in a packing-case… nailed up cabin pockets and tidies on the posts of the hut, fenced off small areas as hanging wardrobes… selected a centre of the hut for dining room, and turned a packing case upside down for a table; unstrapped my deck-chairs and fell into one with an ecstatic grunt’.

There developed a routine. Cara cooked and cleaned and washed clothes herself. She ‘gossiped with the natives near the drill or in their huts, collected flowers, gathered shells, and bathed in the lagoon’. Conversation was possible at first, no doubt, because of missionary contact but Cara later learned Samoan. She became the island doctor and nurse to both whites and locals, treating ulcers and ringworm and discouraging the eating of pork because of biliousness it apparently caused. There were alternatives to pig. Coconuts were plentiful, vegetables grown in gardens and seafood caught in what seemed like sustainable abundance. ‘Fish generally in Funafuti have a bad time of it’, Cara noted wryly, ‘they are hooked, speared, netted, and trapped, and yet in spite of all these drawbacks they manage to increase and multiply exceedingly’.

Cara went to church, as one may expect, but with nothing like the dedication of the local people. ‘I never saw people more reverent at prayer and at Holy Communion’, she noted. She remarked upon the significance of hat wearing for women at church. That is especially interesting for here was a ‘tradition’ still new and yet well-established. Woven hats were a legacy of the missionary emphasis upon respectable attire for worship in the islands. Local people took to it with alacrity as weaving was a skill spread throughout the Pacific, particularly where pandanus grew. Mats were woven to wear and to use as roofs and walls. Weaving created baskets, fish traps and sails. On Kiribati, warriors wore armour made from thickly woven cocoanut fibre. The tradition of making and wearing woven hats for church is still alive and well. In French Polynesia the headwear is called ‘Taupoo’ and in the Cook Islands it is ‘Rito’.

Hats were proper but the wearing of flowers were not. Neither were locals encouraged to ‘dance on their feet’, which I assume allowed some swaying to the rhythm while seated. Puzzled, and I suspect put-off, by ‘these puritanical restrictions’, Cara asked the visiting white missionary about their origin and purpose. He explained that ‘Samoans dressed in wreaths of flowers for their native dances, that these dances lasted all night, and developed into obscene and licentious orgies of an indescribable nature’. The restrictions were imposed by white missionaries on Samoa but then exported by local pastors to Ellice Island. Christianity had become so embedded within Polynesian society – the first London Missionary Society vessel arrived in Tahiti in 1797 – that islander on islander evangelism was widespread by the late 19th century.

The world for Ellice Islanders had expanded dramatically in the 50 years before Cara’s visit. Long part of a regional Pacific economy, by the end of the 19th century they were incorporated into a global culture of religion, science and trade. And yet the islanders embraced the people who turned up on their doorstep with apparent equanimity. They coined a word for Britannia, ‘Peritania’, and one for Sydney, ‘Sini’. There may have existed a sense of common humanity before the arrival of the missionaries but if so that was now expressed in terms of Empire, biology and the Christian god. ‘We, the people of Funafuti, are all very glad to see you here to-night at our sing-sing’, was the welcome given to Caroline, Edgeworth and others on one evening of song, ‘we are all friends, we are under the same Queen, we obey the same laws, and we worship the same God. There are black men and white men, and red men, but the heart and the blood are the same…’ Such an expression of equality cut across the hierarchies that were justifying colonisation across the world, scientific racism in particular.

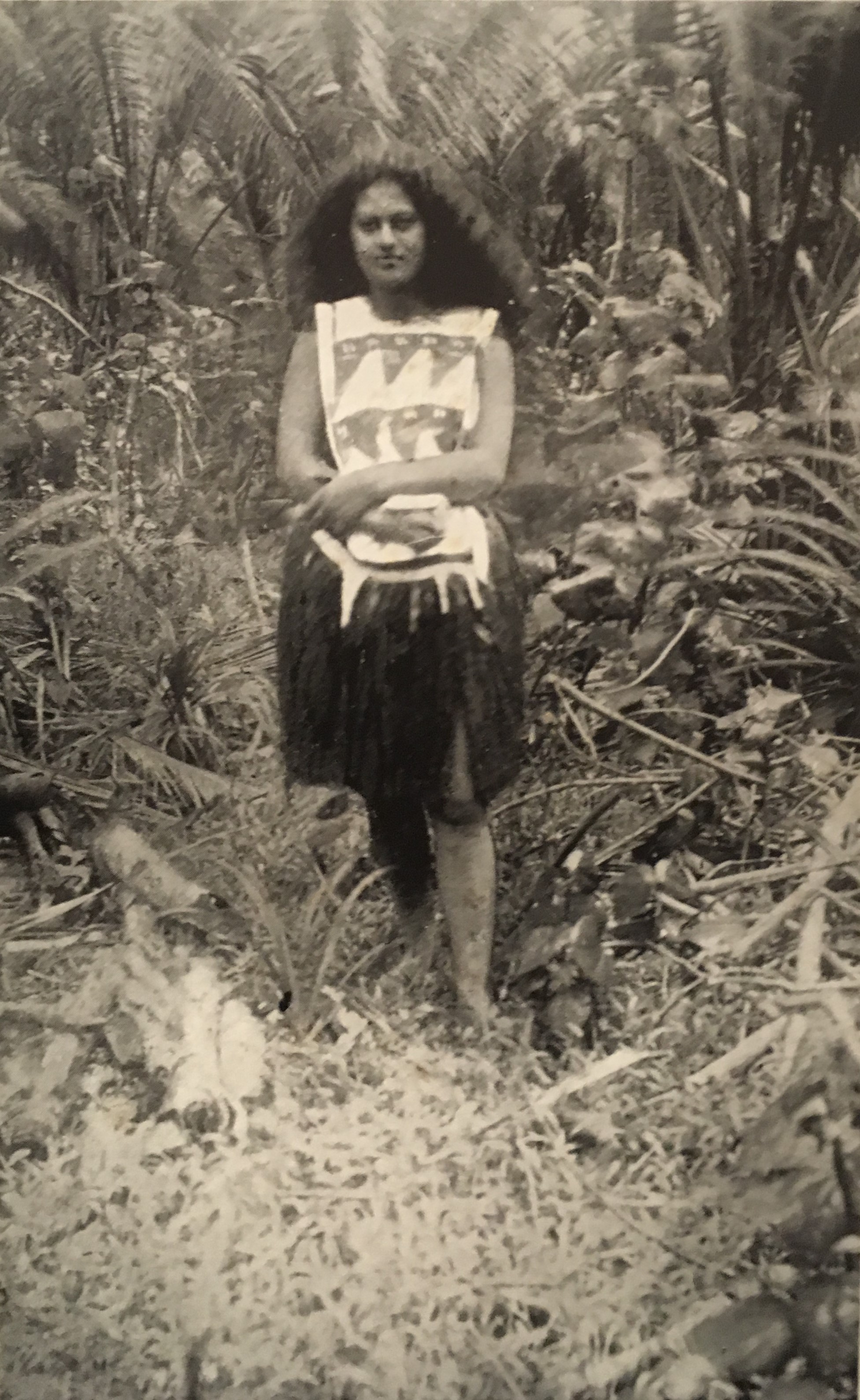

Cara David seems to have received this openness with respect. Absent is any sense of superiority so often evidenced by drollness and irony in British commentaries. ‘Orphans and strangers were we when we landed at Funafuti, but in a very short time we had numerous official friends and quite a formidable array of relatives’. By that she was referring to the local custom of non-biological kinship, sometimes called ‘fictive kinship’ by anthropologists. A local woman called Tufaina became a ‘mother’ to the Englishwoman. In Cara’s words: ‘she told me that I was good, that she loved me, that she was my mother. I thanked her, said that I loved and respected her and was proud to be her daughter’. Cara herself became a mother to younger locals. She counted all the island women as her friends but singled out Peke ‘the trader’s handsome daughter’, Solonaima, and Tavaū ‘as the closest’.

Just as the British brought changes to Funafuti, island life seems to have changed Cara in the months she was there. When she, like the other loyal subjects, observed Queen Victoria’s Jubilee Day with a chorus of ‘God Save the Queen’, Cara did so, ‘to a tune of my own – I’d forgotten the right one’.

Cara went on to become President of the National Women’s Movement and a State Commissioner for the Girl Guides Movement.

More from the collection later…..